What does the Epstein zeta function actually do?

Published:

When I first started studying mathematics at university, I was obsessed with popular math problems, such as the Riemann Hypothesis. The conjecture states that all zeros of the Riemann zeta function other than \(-2, -4, -6\), … lie on the critical line \(\operatorname{Re}(\nu) = 1/2\). If proven, this would earn you a million dollars 💸

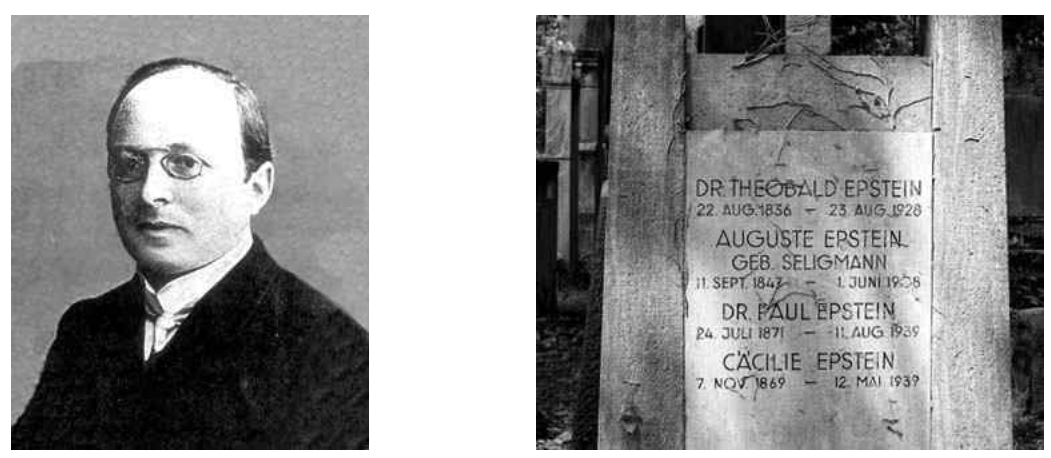

Unfortunately, I feel my chances of winning that prize are better by playing the lottery1 🍀 so thankfully, I’m not working on this problem. However, my research is somewhat related. The Epstein zeta function, derived in 1903 23 by the Jewish mathematician Paul Epstein, generalizes the Riemann zeta function to higher dimensions.

For \(\operatorname{Re}(\nu) > 1\), the Riemann zeta function takes the simple form \[ \zeta(\nu)=\sum_{z=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{z^{\nu}} ,\qquad \operatorname{Re}(\nu)>1. \] Even in one dimension, the Epstein zeta function has three more parameters: A rotation \(y\in\mathbb R\), a shift \(x\in\mathbb R\) and a scale factor for the integers \(c>0\) \[ Z_{c\mathbb Z,\nu} \genfrac||{0pt}{0}{x}{y}=\sum_{z=-\infty}^{\infty}’\frac{e^{-2\pi i (cz)\cdot y}}{(cz-x)^{\nu}} ,\qquad \operatorname{Re}(\nu)>1 \] where the primed sum signifies the exclusion of \(cz = x\). The Millenium problem regarding the zeros at \(\operatorname{Re}(\nu)=1/2\) arises when \(\nu\in \mathbb C\setminus \{1\}\), where both functions are extended using its so-called meromorphic continuation, which is outside the scope of blog post for a general audience.

Epstein, who later committed suicide in fear of persecution by the Gestapo, already derived most of the results we are working with today. This is incredibly impressive, and his work deserves to be more widely recognized, which is one of my reasons for writing this.

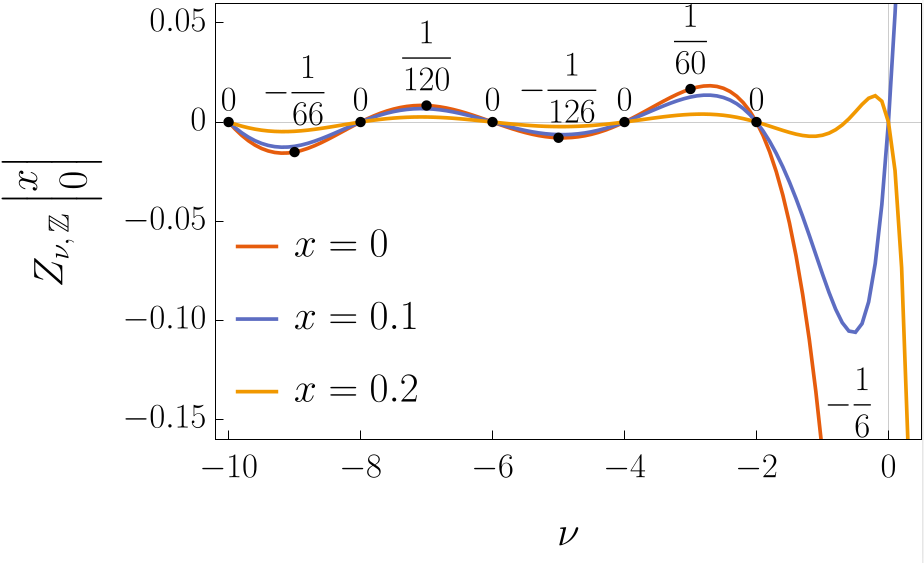

You can actually see these trivial zeros \(-2, -4, -6\) of the Riemann zeta function in the plot of the blue line (Epstein zeta at \(x = y = 0\) and lattice \(\mathbb{Z}\) = two times Riemann zeta). Note that the Epstein zeta function shares these zeros for other values of \(x\) too!

Visualization of the one-dimensional Epstein zeta function as a function of the exponent \(\nu\) for \(y = 0\) and various values of \(x\). Created by the author. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.**Plot of the one-dimensional Epstein zeta function as a function of the exponent \(\nu\) for \(y = 0\) and various values of \(x\). Created by the author. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Visualization of the one-dimensional Epstein zeta function as a function of the exponent \(\nu\) for \(y = 0\) and various values of \(x\). Created by the author. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.**Plot of the one-dimensional Epstein zeta function as a function of the exponent \(\nu\) for \(y = 0\) and various values of \(x\). Created by the author. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Interestingly, the Epstein zeta function isn’t just relevant to number theory (the research area where the Millennium Problem is situated). It also plays a crucial role in physics, particularly in systems involving sums over large numbers of particles. One notable example is the Casimir effect, which was predicted in 19484 and later experimentally confirmed. The reason for this is quite technical; you might encounter it after about six semesters of studying physics, in an introduction to quantum field theory at university. Surprisingly, the calculation can be expressed in terms of the Epstein zeta function!

In short, the total energy \(\mathcal E\) between the plates is given by \[ \mathcal E(\Lambda) = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{\boldsymbol k} \lambda_{\boldsymbol k}^{-\nu} \] in the sense of evaluating the meromorphic continuation in \(\nu \in \mathbb C\) of the lattice sum at \(\nu = -1\). \(\boldsymbol k\) is a wavevector, and \(\lambda_{\boldsymbol k}\) are the eigenvalues of a massless Klein-Gordon equation (you can read about this in detail in our paper5). The important bit: This can be expressed in terms of the Epstein zeta function as \[ \mathcal E(\Lambda) = \pi Z_{\Lambda^{-T}, -1} \genfrac||{0pt}{0}{\boldsymbol x}{\boldsymbol y} \] as one can, among others, learn from the famous Steven Hawking6 and Stephen Wolfram7, the latter being the founder of Mathematica, my favorite programming language, in which I created the visualization!

Here’s how it works: Imagine two perfectly conducting plates in a vacuum, placed extremely close to each other. Classical physics predicts that nothing will happen since it’s a vacuum. But in the realm of quantum physics, the opposite is true: quantum fluctuations cause an attractive force between the plates, effectively pushing them together. This result is truly surprising and counterintuitive, since intuition says that there is nothing in the vacuum to act on the plates! The underlying calculation involves advanced techniques, but at its core, it can be expressed using the Epstein zeta function. This is just one example of how my favorite special bridges the gap between abstract theory and real-world phenomena ✨

So, why does this matter for researchers in physics? Before our work, if someone wanted to calculate the Epstein zeta function for a specific physical scenario, they would likely have to sift through expensive, specialized books on lattice sums (such as this one8), hoping to find a relevant case 😓 Now, we’ve solved this problem by developing a free, open-source software library9 that efficiently calculates the Epstein zeta function for any real parameter 🚀 In our preprint5, we discuss the properties of this function and how it can be applied to a variety of physical systems.

Paul Epstein (1871–1939), the mathematician who derived the Epstein zeta function. Image source: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, Scotland. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Paul Epstein (1871–1939), the mathematician who derived the Epstein zeta function. Image source: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, Scotland. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

References

Riemann Hypothesis - Numberphile “The most difficult way to earn a million dollars” ↩

P. Epstein. “Zur Theorie allgemeiner Zetafunctionen”. In: Math. Ann. 56 (1903), pp. 615–644. url: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01444309. ↩

P. Epstein. “Zur Theorie allgemeiner Zetafunktionen. II”. In: Math. Ann. 63 (1906), pp. 205–216. url: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01449900. ↩

Hendrik BG Casimir. “On the attraction between two perfectly conducting plates”. In: Indag. Math. 10.4 (1948), pp. 261–263. ↩

Andreas A Buchheit, Jonathan K. Busse, and Ruben Gutendorf. “Computation and properties of the Epstein zeta function with high-performance implemen- tation in EpsteinLib”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.16317 (2024). ↩ ↩2

: Stephen W Hawking. 1977. Zeta function regularization of path integrals in curved spacetime. Communications in Mathematical Physics 55 (1977), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01626516 ↩

Jan Ambjørn and Stephen Wolfram. 1983. Properties of the Vacuum. I. Mechanical and Thermodynamic. Annals of Physics 147, 1 (Aug. 1983), 1–32. doi:10.1016/0003-4916(83)90065-9 ↩

J. Borwein et al. Lattice Sums Then and Now. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications. Cambridge University Press, 2013. url: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139626804. ↩

https://github.com/epsteinlib/epsteinlib ↩